Black drivers in Hampton Roads and across Virginia are more likely to be stopped and searched by police than any other racial or ethnic group, according to data just released as part of the new Virginia Community Policing Act.

The state law requires police to collect and report information on every traffic stop they perform. That includes demographic information of the driver, why the car was stopped, whether a warning or citation was issued, if the driver was arrested and whether any person or the vehicle was searched. The release marks the second time data has been shared publicly under the law, which was passed in the General Assembly in 2020.

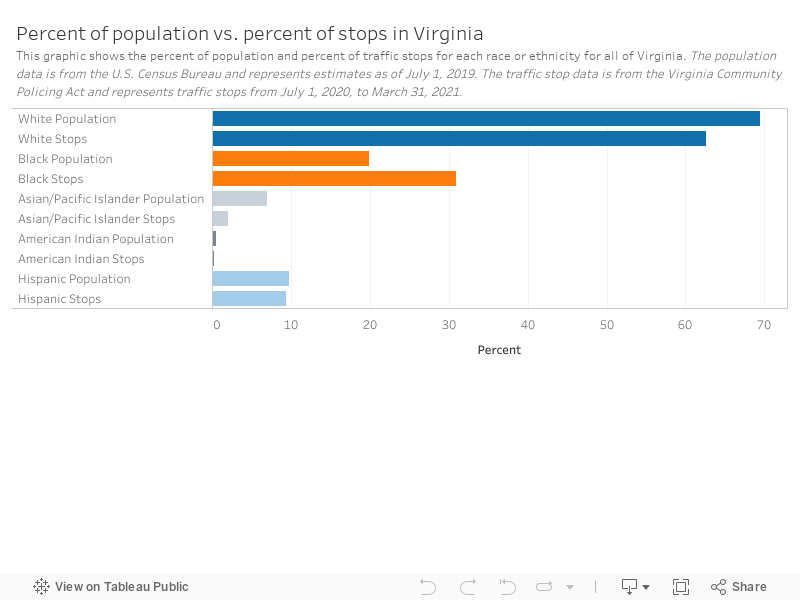

A Virginian-Pilot analysis of the data shows that statewide, Black drivers are the only racial or ethnic group in the state that are stopped by police at a higher rate than their share of the population.

Black drivers accounted for about 31% of traffic stops statewide, despite making up 20% of the state’s population. White drivers made up 63% of stops statewide, though whites are 69% of the population.

“The news story isn’t that Virginia is particularly bad or Virginia is particularly good,” said Frank Baumgartner, a political science professor at UNC-Chapel Hill, whose research analyzes similar traffic stop data in North Carolina. “It’s that Virginia is a part of the United States and it has this racialized policing pattern that we see everywhere.”

The data is maintained by Virginia State Police and includes information on more than 657,000 traffic stops conducted by 307 police agencies across the state between July 1, 2020, and March 31, 2021.

var divElement = document.getElementById(‘viz1626453361485’); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName(‘object’)[0]; if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 800 ) { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’;} else if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 500 ) { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’;} else { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=’727px’;} var scriptElement = document.createElement(‘script’); scriptElement.src = ‘https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js’; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);

Hispanic drivers made up about 9% of stops, roughly equal to their 10% share of the population. Asian and Pacific Islander drivers made up 2% of stops and represent about 7% of the state’s population.

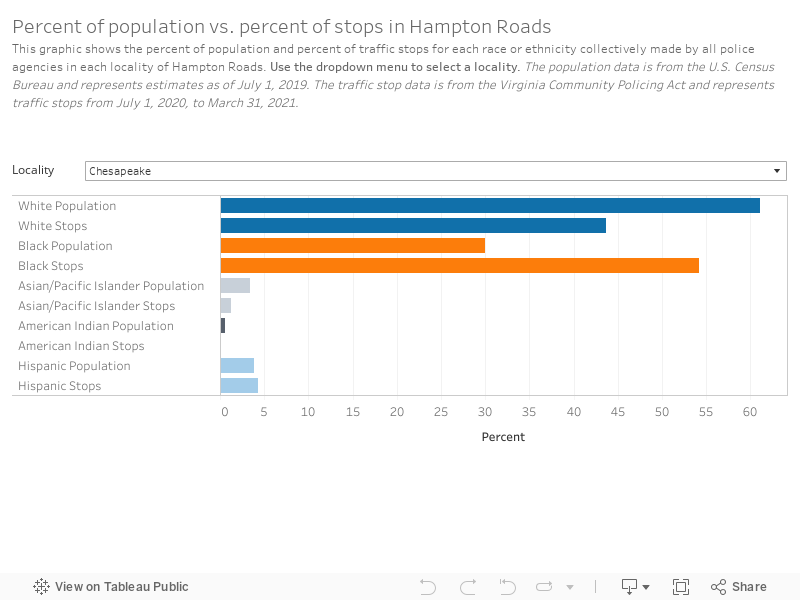

Police agencies in 16 Hampton Roads localities stopped Black drivers at a higher rate than the share of the Black population in those localities. Fifteen localities in Hampton Roads had a greater disparity than the state’s difference of 11%.

In at least five Hampton Roads localities, the percentage of Black drivers stopped was at least twice the percent of the Black population in the locality. For this story, The Pilot contacted 15 police agencies in Hampton Roads for comment on their agency’s data. Eleven agencies responded, either by email statement, phone or an in-person interview.

var divElement = document.getElementById(‘viz1626453890156’); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName(‘object’)[0]; if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 800 ) { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’;} else if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 500 ) { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’;} else { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=’727px’;} var scriptElement = document.createElement(‘script’); scriptElement.src = ‘https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js’; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);

Part of larger trends

The data from the Community Policing Act does not include information on whether the driver who was stopped is a resident of the locality where they were stopped, and some agencies in Hampton Roads, such as those that patrol major highways and thoroughfares, or those that are located in tourist destinations, were quick to dispute possible racial disparities that the data revealed.

The Chesapeake Police Department made the fourth-most stops of any police agency in the state. Of the roughly 18,000 stops the agency made during the nine-month timeframe, 54% were of Black drivers. The population of Chesapeake is approximately 30% Black, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Chesapeake Police Department public information officer L.C. Kosinski said in an email that many non-Chesapeake residents use the roads in Chesapeake daily, whether for traveling to work or to run errands.

“Many drivers in Chesapeake are residents of Hampton Roads, but not necessarily of Chesapeake — creating some difficulty when trying to overlay the demographics of the traffic stops over Chesapeake’s population alone,” Kosinski wrote.

Still, Baumgartner said, the disparities in Hampton Roads and Virginia can be seen as part of a larger trend in policing, in which traffic stops are not only used to enforce the rules of the road, but also to track and crack down on violent crime, or to seize contraband — which can disproportionately affect people of color, and specifically young men of color.

In an interview with The Virginian-Pilot, Newport News Police Chief Steve Drew said he generally places more patrol officers in areas with high crime rates. Drew said that those areas tend to have high poverty rates and more people of color.

Because more officers are present in those areas, Drew said, it can lead to more people of color being stopped.

“I want to make sure, it’s important that we’re not just stopping one group of people. I’m not seeing citizens in our city complain about that. Our number one complaint is demeanor,” Drew said. “But I do use traffic enforcement as a way to address violent crime. Absolutely.”

Of the roughly 9,700 traffic stops Newport News police officers made during this timeframe, approximately 63% were of Black drivers. Newport News is 41% Black, according to 2019 estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Drew said that he tries to balance the heavy police presence in certain communities with increased community outreach efforts.

Based on his research, Baumgartner said that since about the 1960s or ’70s, some police have viewed traffic stops as a way to legally prompt a conversation with drivers about any weapons, drugs or other contraband they may have in the car. The Supreme Court has upheld that when an officer stops a driver for a traffic violation, it may be reasonable to search the vehicle under the Fourth Amendment.

“I don’t want to minimize traffic safety. It’s important to teach people to drive in a responsible manner,” Baumgartner said. “The part where it gets into difficulty and where the racial disparities come in is when we divert the traffic control function, traffic safety function into the war on crime.”

Statewide, only 3% of stops during the timeframe that the data represents resulted in a search of the driver’s vehicle. Of the drivers whose vehicles were searched, about 68% were Black.

Drew said that he could not provide specific reasons why an officer in his agency might search a vehicle.

“A lot of that depends on what they see at the time of that stop,” Drew said.

Baumgartner said that the numbers aren’t surprising.

His research, which analyzed some 20 million traffic stops made in North Carolina over about 20 years, shows that Black drivers in North Carolina are about twice as likely to be stopped, compared to white drivers, even though Black drivers are estimated to drive 16% less often than white drivers.

Similar research by the Stanford Open Policing Project found that nationwide, Black drivers are about 20% more likely to be stopped than white drivers.

___

Do police use the data?

Under the Community Policing Act, the state Department of Criminal Justice Services is required to release an annual report analyzing the data. The first report is expected to be released in the coming weeks.

State Del. Luke Torian, D-Prince William, who introduced the legislation, didn’t want to comment on The Pilot’s analysis until the report is released by the criminal justice department, though he said that he was “not surprised” by the preliminary data he had seen.

“And it just further solidifies our suspicions and also the recognition that this is a policy and practice that’s needed,” he said.

But even after the department releases its report, it remains unclear whether police agencies will use the data and subsequent findings to inform their policing practices.

The Community Policing Act prohibits officers from engaging in “bias-based policing” — defined in the law as taking action solely based on a person’s race, ethnicity, age or gender — but does not define a specific threshold in the data at which an agency or an individual officer might be suspected of doing so. The law does not give guidelines or instructions for how agencies should use the data.

Several Hampton Roads police agencies, including in Chesapeake and Newport News, said that they regularly review data, including traffic stops, as a way to monitor and improve their practices.

Drew said that the Newport News Police Department reviews data twice a week.

“We’re very, very data driven in this department. I think we have to be evidence-based and data-driven, so every Monday and every Thursday, we go over our data points, if you will,” Drew said. “Because I think it’s important how we hold ourselves accountable and take ownership of what we’re doing in this organization. We have to be able to back it up.”

Kosinski said in an email that the Chesapeake Police Department reviews the traffic stop data monthly and that the agency “knows how important it is that our officers are aware of this data, to ensure we are practicing fair and impartial policing.”

In a phone call, he said that he was not sure how officers are made aware of the data, but that it could be done through “roll call training,” in which command officers disseminate it to lower-level officers.

Police officers are required to have 40 hours of in-service training every two years. Two hours of that must be devoted to “cultural diversity” training.

As of July 1, officers are required to report additional information on the traffic stops they perform, including whether the person who was stopped spoke English and whether the police officer used force during the stop.

Torian said that he hopes agencies will take it upon themselves to analyze the data and improve their practices as needed. He said he did not know of any future legislation based on the data.

“I trust that they will hopefully do the right thing, and when they see that there is a problem, that they will implement training to address it,” he said.

Korie Dean, korie.dean@virginiamedia.com