“If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed for you.” It’s a familiar phrase, but what does “appointed” really mean? In many jurisdictions in the United States, even after a judge appoints counsel for you, you may spend days or weeks in jail before you actually meet your lawyer. In new research, Alissa Pollitz Worden, Kirstin Morgan, Reveka Shteynberg and Andrew Davies study New York State-funded programs which ensure lawyers are present at defendants’ first court appearances (which is when judges make bail and pretrial detention decisions). They find that the presence of these lawyers may reduce the numbers of people jailed pretrial in misdemeanor cases. This in turn may mean lower incarceration costs for local governments and reduce the social harm of pretrial detention for defendants.

“If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed for you.” It’s a familiar phrase, but what does “appointed” really mean? In many jurisdictions in the United States, even after a judge appoints counsel for you, you may spend days or weeks in jail before you actually meet your lawyer. In new research, Alissa Pollitz Worden, Kirstin Morgan, Reveka Shteynberg and Andrew Davies study New York State-funded programs which ensure lawyers are present at defendants’ first court appearances (which is when judges make bail and pretrial detention decisions). They find that the presence of these lawyers may reduce the numbers of people jailed pretrial in misdemeanor cases. This in turn may mean lower incarceration costs for local governments and reduce the social harm of pretrial detention for defendants.

The United States Constitution requires courts to provide legal counsel to indigent persons accused of misdemeanors, but it does not guarantee immediate access to counsel. Just fourteen states guarantee the presence of an attorney at a defendant’s first court appearance, and in at least one of those, New York, that guarantee is often not fulfilled in practice. Yet at the first appearance the stakes are high: at this hearing a judge formally specifies the charges (“arraignment”), and decides whether the defendant will be detained pending his or her case’s conclusion (contingent on their ability to make the judge’s bail), or will be free (released on their own recognizance or under the supervision of probation). Before trial, of course, defendants are presumptively innocent, meaning detention requires special justification. And yet, without counsel, most are unequipped to challenge that detention.

Pretrial detention has a range of negative consequences. Defendants who are detained before their trial may be more likely to plead guilty than those not detained, even if their charges and circumstances are similar. They may also find it harder to find employment after they are released, and be more likely to commit future crimes. Meanwhile the costs of pretrial detention for taxpayers are significant, with one recent analysis suggesting it would be possible to reduce significantly the cost of pretrial detention without impacting public safety.

Our research examines the impact of a program in upstate New York designed to provide counsel at first appearance (CAFA) in court to persons facing misdemeanor charges. Counties’ indigent defense programs were funded to design and implement initiatives tailored to their local challenges and strengths, allowing them to address the complicated logistical problem of getting lawyers to courts at short notice. We examined whether the presence of CAFA – that is, the physical presence of a lawyer at the defendant’s side – could change judges’ decisions to detain, release, and set bail. We compared detention outcomes before CAFA was introduced to those immediately after its introduction in three pseudonymous counties, ‘Bleek,’ ‘Lake,’ and ‘Hudson.’

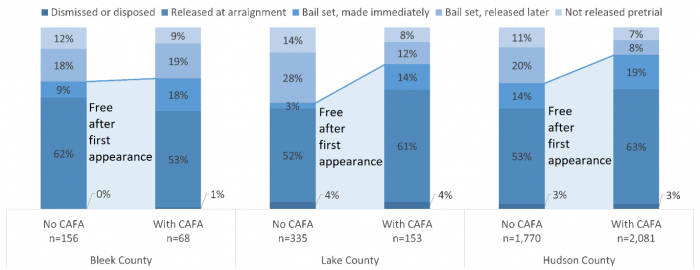

We found significant changes in all three counties. Highlighted in Figure 1 are the proportions for those ‘free after first appearance’ – that is, either released on their own recognizance (ROR) or under supervision, released following payment of bail or bond, or released following the dismissal or disposition of their cases. Our statistical tests showed that in Hudson County the number of people released without any conditions increased significantly.

Figure 1 – First appearance outcomes in three New York counties before and after the introduction of CAFA

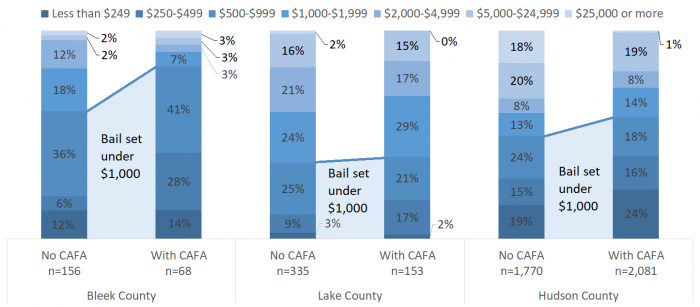

As Figure 2 shows, the numbers of defendants for whom bail was set at lower and more manageable amounts increased significantly in Bleek and Hudson Counties. Overall, defendants were 10-20 percent more likely to have bail set under $1,000 in both counties when counsel was present at their first court appearance. In Bleek County, defendants were three times more likely to have bail set under $500 with CAFA. Discussion with defense attorneys in all three counties suggests that there is consensus that most defendants would find any bail above $500 difficult to meet.

Figure 2 – Bail amount outcomes in three New York counties before and after introduction of CAFA (bail cases only)

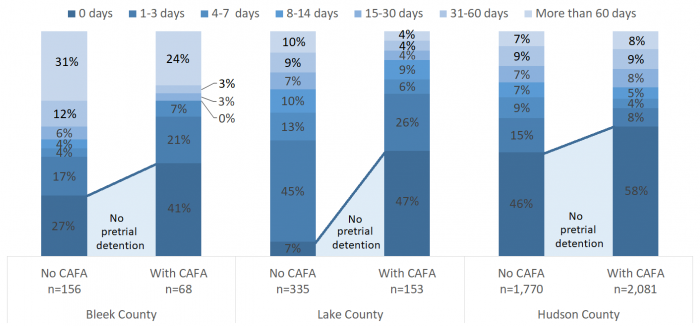

Figure 3 shows how the number of defendants avoiding pretrial detention increased significantly in Lake and Hudson Counties. Most notably, in Lake County, defendants (for whom bail was set) were approximately seven times more likely to avoid any pretrial detention when counsel was present.

Figure 3 – Time in pretrial detention among persons for whom bail was set in three New York counties before and after introduction of CAFA

Across these three counties, with CAFA in place, judges made decisions about bail and pretrial detention that were, in the aggregate, less restrictive. More defendants had lower bail set and, perhaps as a result, more defendants avoided or decreased their pretrial detention.

Our results suggest two things. First, having counsel present at first appearances can change the pattern of decisions judges make. Judges may release more people with fewer conditions, and impose fewer financial barriers upon those from whom they demand bail, with the cumulative result that fewer people will be detained pretrial. Second, having counsel present may ultimately save incarceration costs – often rated at over a hundred dollars per inmate per day – which could save counties and other local governments money.

“Bad Apple Bail Bonds” by a-birdie is licensed under CC BY NC 2.0

Our results do not answer certain remaining questions. Why did judges change their decisions in these ways? Is it that lawyers are making persuasive arguments? Does their presence mean judges here a more cohesive and less incriminating narrative about defendants? Or is it something else? On the other hand, are there implications for public safety in the release of more people in this way? And what are the preconditions within counties that will allow for successful implementation of these kinds of reforms? As we’ve written elsewhere, reforming court processes can be hard work, and often ends in failure.

Pretrial detention may be necessary in some cases. But a balance must be struck between public safety concerns and the harms that occur to defendants when they are detained. Judges should have ample opportunity to consider the circumstances of each person brought before them. Having a lawyer present to articulate the case for release is not only a way to secure the guarantees of the Sixth Amendment, therefore. It may also be a way to give judges the tools they need to make better decisions about sending people to jail before trial.

You can visit the Counsel at First Appearance (CAFA) project website to learn more about the project and other related papers.

- This article is based on the paper, “What Difference Does a Lawyer Make? Impacts of Early Counsel on Misdemeanor Bail Decisions and Outcomes in Rural and Small Town Courts,” in Criminal Justice Policy Review.

- The CAFA Project was supported by Award 2014-IJ-CX-0027 from the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. This paper was commissioned by the Misdemeanor Justice Project—Phase II, sponsored by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this article are those of the authors and are not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics, nor do they reflect those of the Department of Justice, the New York State Office of Indigent Legal Services, nor do they reflect the official position or policies of the Laura and John Arnold Foundation and the Misdemeanor Justice Project.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2PLA62f

About the authors

Andrew L. B. Davies – New York State Office of Indigent Legal Services

Andrew L. B. Davies – New York State Office of Indigent Legal Services

Andrew L. B. Davies is the Director of Research in the New York State Office of Indigent Legal Services. He is responsible for pursuing research and data collection to monitor, study, and make efforts to improve the quality of defense services in that state.

Reveka V. Shteynberg – University at Albany

Reveka V. Shteynberg – University at Albany

Reveka V. Shteynberg is a Doctoral student in the School of Criminal Justice at the University at Albany, State University of New York. Her research focuses on criminal courts and criminal justice reform, particularly as it relates to plea bargaining, bail and pretrial detention, juror decision-making, juvenile justice, and policy and program evaluation.

Kirstin A. Morgan – Appalachian State University

Kirstin A. Morgan – Appalachian State University

Kirstin A. Morgan is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Government and Justice Studies at Appalachian State University. Her research interests are juvenile justice, perceptions of criminal justice, criminal court culture and reform, policy and program evaluation, involvement in and responses to youth street gangs, and research methods and design.

Alissa Pollitz Worden – University at Albany, State University of New York

Alissa Pollitz Worden – University at Albany, State University of New York

Alissa Pollitz Worden is an Associate Professor in the School of Criminal Justice at the University at Albany, State University of New York. Her research addresses justice policy, court decision making, indigent defense systems, and public perceptions of crime and justice.